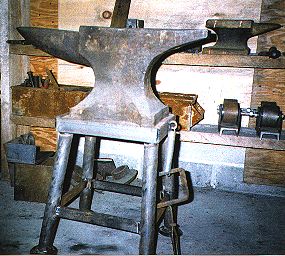

The threaded rod actually clamps the anvil in place. There are no nails or shims and the anvil sits on a bed of silicone caulking (really If you look at the ends of the anvil stand you will notice the 1/2" threaded rods that hold the thing together. I suggest using yellow carpenter's glue and glue coated nails. I'd forgotten that Steve's end boards were 1-1/2" taller than the others to retain the anvil.Įach board is offset about 1-1/2 to 2" as they are stacked up. NOTE: When I was making my drawing below I had not looked at this photo for a year. The unique and HANDY thing about this design is the offset Steve put in the pieces as he stacked them up.

It is a solid section built up by laminating pieces of 2x12 framing lumber. This anvil stand was built by Steve Barringer of B2 Design in Mooresville, NC. There are numerous ways to build an anvil stand. OR have them available when we NEED a stand. Often after wind or ice storms you can have your choice of log sections if you ask and have a way to haul them home.ĭon't forget that a taller section of log is a handy stand for a swage block OR to carve depressions in the end for forming sheet metal.īut, we are not always so lucky to have windfalls of large logs available OR the chain saw to cut to size. The piece of oak was collected after an ice storm. This old German anvil is setting on an oak stump that was trimmed to fit. Most modern smiths prefer some degree of portability. When you do this you want to be VERY sure that you will not want to change your anvil location.

In old shops with permanent forge and anvil locations longer sections of logs like this were often set deep in the ground. I prefer to be able to lift mine off the stand if needed. Some smiths strap their anvils down to reduce the ring. Usually there are some spikes driven in the stump to keep the anvil from walking off from vibration. This is a short section of log that sets on the ground and the anvil sets on top. The Peter Wright anvil on a red oak stand at top is a classic.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)